Part 2 of a series

By the TessDrive Team

In part 1 of this comprehensive report, we discussed the many factors—man-made and natural—that cause the perennial flooding in Metro Manila during the monsoon season. Now we focus on two natural factors—geographical and climatological—to drive the urgency of responsible action from society and our government.

Read Part 1 here: https://tessdrive.com/drowning-in-floods-drowning-in-corruption/

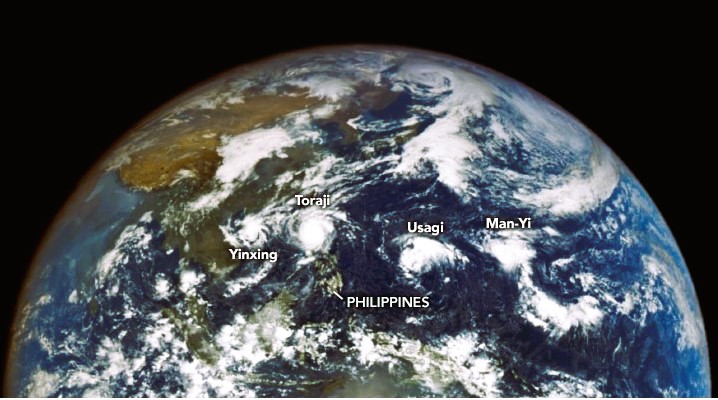

To understand the scale of Metro Manila’s flood crisis, one must first appreciate the profound geographic and climatological context in which the city exists. The region’s baseline exposure to flooding is exceptionally high, a reality dictated by its topography and its location within the world’s most active typhoon corridor. According to ThoughtCo.com, in its report “The 7 Global Hurricane Basins” posted last May 9, nearly a third of the world’s total cyclone activity happens in the western north Pacific region, where the Philippines is located. This area is also where some of the most intense storms are generated. While these natural factors make flooding a constant and inherent threat, they do not, by themselves, explain the escalating severity and widespread devastation witnessed in recent decades. They set the stage for a disaster, but they do not make the current catastrophe inevitable.

Basin by design: A geographic predicament

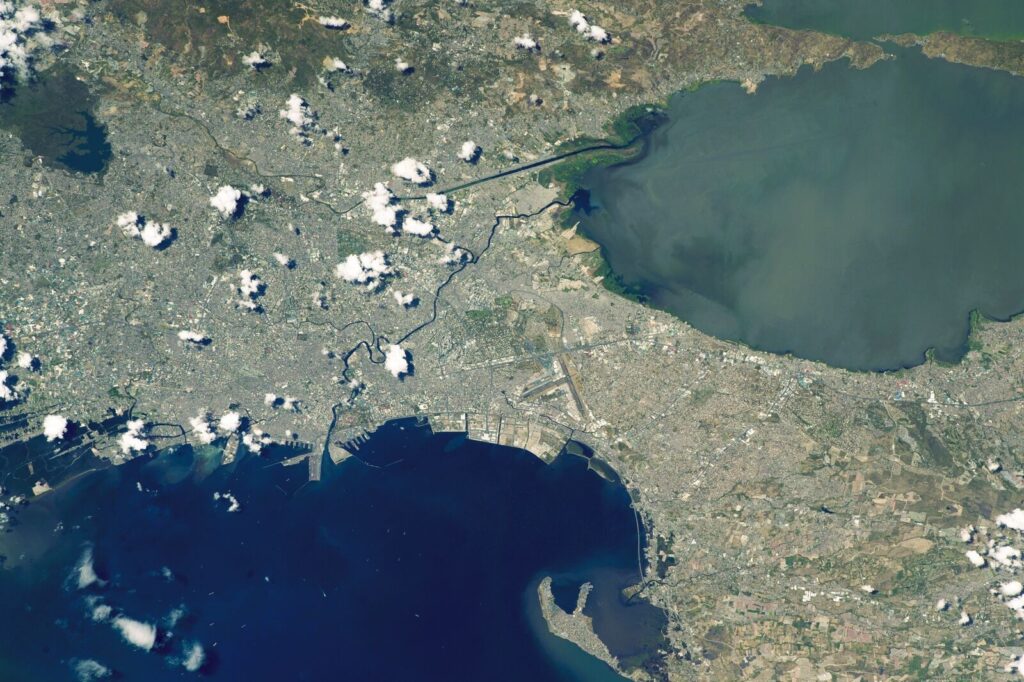

According to Dr. Greg Bankoff in his article “Vulnerability and Flooding in Metro Manila” in the International Institute of Asian Studies online newsletter number 31, Metro Manila is fundamentally a city built on a floodplain. The metropolis occupies a vast, low-lying coastal plain and a semi-alluvial delta, a landscape shaped over millennia by sediment flows from multiple river systems. This topography creates a natural drainage basin, channeling water from the surrounding highlands of Rizal and Bulacan directly into the urban core. The primary river systems that traverse this basin include the Pasig-Marikina River system to the east, and the Malabon-Tullahan and Meycauayan river basins to the north.

The region’s geographic predicament is compounded by its unique position between two massive bodies of water. To the west lies Manila Bay, exposing the city to coastal hazards like high tides and storm surges. To the southeast is Laguna de Bay, the country’s largest lake, which acts as a massive but often overwhelmed temporary holding basin for floodwaters. This positioning makes the National Capital Region acutely susceptible to a complex interplay of flood types: Riverine (or fluvial) flooding from overflowing rivers during heavy rainfall, and coastal (or pluvial) flooding, which includes direct inundation from storm surges and the critical problem of “backflow” when high water levels in the bay or the lake prevent rivers from discharging their load.

Historically, a network of natural channels and estuaries, known as esteros, provided drainage for the area. However, as RC Ladrido reported in the article “Manila’s waterways: Lost and disappearing” posted last Aug. 11 on verafiles.org, these colonial-era waterways are now fundamentally inadequate to serve the needs of a sprawling megacity of over 13 million people. The result is a system under constant strain, where an estimated 20% of the capital’s land area is officially designated as flood-prone.

The climatological reality

The Philippines’ location places it squarely in the crosshairs of extreme weather. The archipelago sits within the Western North Pacific typhoon belt, the most active region for tropical cyclones on Earth. According to the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (Pagasa), an average of 20 tropical cyclones (TCs) enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) each year, with approximately 8 or 9 making landfall or directly impacting the islands. These cyclones are the primary drivers of the heavy, intense rainfall that leads to widespread flooding across the country.

For Metro Manila, the danger is amplified by the seasonal calendar. The peak of the typhoon season, from July through October, coincides with the southwest monsoon, locally known as the Habagat. This creates a potent dual weather system where a passing typhoon, even one not making direct landfall on the capital, can significantly enhance the monsoon rains. This interaction can trigger prolonged periods of extreme precipitation that completely saturate the ground and overwhelm the region’s drainage capacity, leading to severe and sustained flooding.

Pagasa bulletins frequently warn of the enhanced monsoon bringing strong winds and heavy rainfall to Metro Manila, even when the cyclone’s center is hundreds of kilometers away.

The constant refrain about Metro Manila’s “natural” vulnerability, while factually correct, has paradoxically become a barrier to progress. It fosters a narrative of inevitability that can be used, intentionally or not, to excuse decades of systemic inaction and mismanagement. When a problem is framed as an insurmountable “act of God” rather than a failure of human planning and governance, public pressure on officials to deliver long-term, systemic solutions can dissipate. This allows a cycle of failure to persist, where officials point to the “unprecedented” nature of each new storm to explain the failure of existing infrastructure, rather than acknowledging that the infrastructure was fundamentally inadequate for well-understood and predictable risks.

This narrative is directly contradicted by historical evidence. While flooding has been a feature of life in Manila for centuries, its character has changed dramatically. In studies by Pagasa and reports by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, over the past half-century, the extent and severity of these inundations have significantly worsened. Floods that were once confined to predictable, low-lying coastal and riverine barangays now regularly submerge suburban hinterlands, newer urban developments, and the entire shoreline of Laguna de Bay, as observed by the Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA).

Water depths have also steadily increased, transforming a manageable hazard into a recurring catastrophe. This historical escalation cannot be explained by geography or climate alone, as these baseline factors have not changed. It serves as irrefutable proof that the worsening crisis is not natural, but man-made. The baseline risk is inherent, but the escalating disaster is the result of the anthropogenic factors that have reshaped the metropolis for the worse.

Amid the investigation of corruption among contractors and politicians, there are many other reasons that have caused the transformation of Metro Manila’s flood risk from a manageable hazard into a perennial catastrophe. The city itself is sinking due to the gradual lowering of the ground surface. The primary cause is the extensive and largely unregulated extraction of groundwater for residential, commercial and industrial purposes. This was reported by Purple Romero in her report “Asia’s coastal cities ‘sinking faster than sea level-rise’” posted April 26, 2022 on preventionweb.net.

This, and other alarming man-made causes, and how these would magnify the effects of global climate change on Metro Manila flooding, will be the subject of Part 3 of our special report.

End of Part 2