By the TessDrive team

The following article constitutes Part 3 (conclusion) of a 3-part deep-dive into Metro Manila’s perennial, destructive, and deadly floods during the monsoon season. If you missed reading Parts 1 and 2, please click on the following links:

While geography and climate set the stage, the transformation of Metro Manila’s flood risk from a manageable hazard into a perennial catastrophe is a direct result of human actions and inactions. A confluence of environmental degradation, unchecked urban expansion, and systemic governance failures has created a highly fragile urban system. This section dissects these anthropogenic drivers, assigning responsibility based on extensive evidence to directly address the question of what, and who, is to blame for the city’s plight.

Massive concentration of surface runoff

Let’s look at the most obvious, man’s alteration of the environment, often without regard to long-term natural consequences. Natural, permeable surfaces like soil, grasslands, and mangroves, which absorb rainwater and allow it to seep into the ground, have been systematically replaced by impervious materials like concrete and asphalt. According to the report “Modeling future urban sprawl and landscape change in the Laguna de Bay Area, Philippines” posted in the Swiss-based open-access publisher Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI) online portal mdpi.com on April 14, 2017: “The Metro Manila area of the Philippines is one of the most rapidly growing mega cities in the world, and, among other things, Manila’s urban sprawl has threatened the ecology of the agricultural lands located along the urban fringe and increased flood vulnerability in the area.”

Even at a quick glance at a map of Metro Manila, it’s pretty obvious that nearly all of the entire area can already be considered as built-up. The direct consequence of this transformation is a massive increase in surface runoff. Surface runoff is a direct result of rainwater that isn’t absorbed by natural soil. Instead, the massive amounts of rainwater dumped by storms and typhoons that fall on impervious surfaces like asphalt and concrete roads, roofs, and other urban structures become surface runoff. Rain that would have once been naturally absorbed by the landscape now has nowhere to go but into the city’s drainage systems. This torrent of water rapidly overwhelms the network of canals and esteros, which are already antiquated and undersized for a modern megacity, causing them to overflow and trigger flash floods.

Garbage: Clogging waterways one careless dump at a time

As if surface runoffs weren’t enough to already drown us in watery misery, we aggravate the problem so much more by clogging our already inadequate esteros with garbage. A “Philippine Solid Wastes” report posted online by the Philippine Senate in November 2017 indicated that the NCR generated over 9,000 tons of solid waste per day, and projected to go up by 165% by the end of 2025.

A substantial portion of this waste, due to inefficient collection and a lack of proper disposal facilities, never makes it to a sanitary landfill. Instead, it is dumped on streets, in vacant lots, and, most critically, directly into the city’s network of rivers, canals, and esteros. In the report “MMDA collects 600 tons of garbage in NCR streets, pumping stations” by Raymond Carl dela Cruz for the Philippine News Agency, posted online last July 23 at pna.gov.ph: “A total of 526.8 tons of garbage were collected from NCR’s 71 pumping stations from July 18 to 22, in addition to 26.37 truckloads or 76.923 tons of garbage hauled from cleanup operations from various areas in NCR from July 21 to 22.”

Sierra Madre, the first line of defense, ravaged

The forests of the Sierra Madre and its foothills, particularly at the Upper Marikina River Basin watershed, act as a giant natural sponge, absorbing immense quantities of rainfall, slowing runoff, and preventing soil erosion. This natural protection has been severely compromised. Decades of deforestation, driven by illegal logging, slash-and-burn farming (kaingin), industrial quarrying, mining operations, and the conversion of forest land for real estate and agricultural use, have stripped large areas of their tree cover. A report by Mikhail Flores of the Agence France-Presse titled “Wetter storms, deforestation: Manila faces worsening floods” posted Feb. 22, 2023 at philstar.com stated: “Only 2.1% of the watershed was covered by dense ‘closed forest’ in 2015, according to a World Bank report.”

The combination of these three key factors—uncontrolled surface runoff, clogged waterways due to garbage, and the deforestation of surrounding forests—completes a recipe for utter disaster. What’s worse is that global climate change is intensifying the risks, upping the stakes, and ultimately multiplying the tragic consequences.

Warmer planet, fiercer storms

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a fundamental consequence of a warming planet is a more intense water cycle. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, which translates into heavier rainfall events. This is not a future projection but a current reality for the Philippines. Guillermo Luz’s Business Matters column posted last May 15 in inquirer.net, titled “State of Climate Change 2025,” said: “The Oscar M. Lopez Center estimates that higher temperatures are likely to increase rain volume by as much as 40%.” Climate models used by the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank consistently project a continued increase in mean and extreme precipitation for the country. No doubt, this will overwhelm an already inadequate urban drainage system.

The scientific consensus suggests that while the total number of tropical cyclones may not necessarily increase in a warmer world, the intensity of the storms that do form is likely to grow. This means an increased frequency of powerful typhoons with higher maximum wind speeds and, critically for flooding, the capacity to dump even greater amounts of rainfall in a shorter period.

Global warming is causing the world’s oceans to expand and glaciers to melt, resulting in a steady increase in global mean sea level. This phenomenon is not uniform across the globe, and analyses corroborated by the IPCC, the University of the Philippines, and even the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) show that some parts of the Philippines are experiencing rates of sea-level rise that are above the global average. This rising sea provides a higher starting point for storm surges and daily high tides, making coastal flooding more frequent and severe. Critically, it also impedes the ability of Metro Manila’s river systems to discharge their water into Manila Bay, a phenomenon known as drainage obstruction.

Responsibility for flood management in the capital is scattered across multiple agencies with ill-defined and sometimes conflicting mandates. The Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) is responsible for planning and building large-scale infrastructure. Well, by now we all know where the supposed funds for these infrastructure went. The Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) is tasked with operations and maintenance, including cleaning drainage systems. The DENR is in charge of watershed management. And the 17 individual LGUs are responsible for local drainage, solid waste management, and enforcing land use plans. This institutional chaos makes a cohesive, basin-wide approach to flood management virtually impossible.

This fragmented system incentivizes the pursuit of “stand-alone” or “piecemeal” projects—a new drainage line here, a small revetment there—that may provide temporary, localized relief but do nothing to address the systemic nature of the problem. Worse, as the current Senate investigations are revealing to an appalled public, many of these projects are built with substandard quality, and worst of all, they don’t get built at all, yet the funds have been magically pocketed by contractors and DPWH officials in cahoots with one another and with government executives. The system is not only fundamentally flawed and ineffective, it has mutated into a greedy monster.

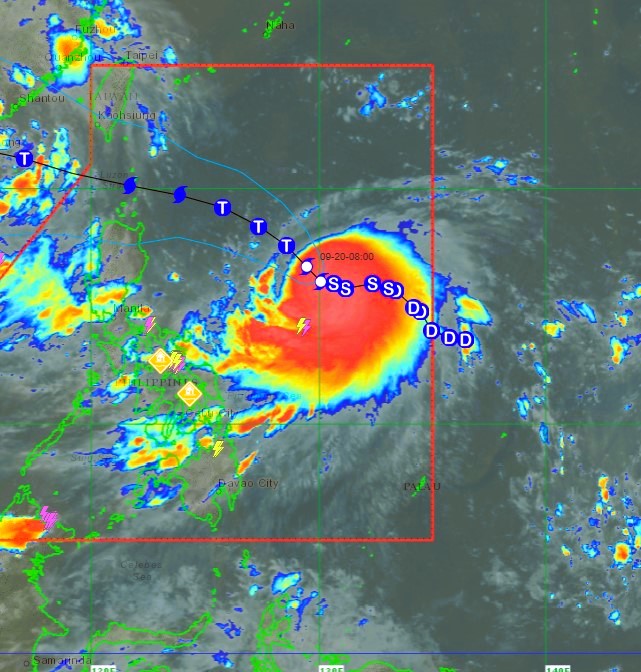

(Image from pagasa.dost.gov.ph)

And now, as you read this, another potential supertyphoon is on its way, and drag with it another potential set of tragic stories of loss, death, and destruction. This typhoon is just one of around 20 or so tropical cyclones battering the country year in and year out. And every time, we raise our voices in prayer, in despair, and in consternation to high heavens.

Our prayers have been answered with…more rains, more storms, more floods.

Perhaps we need to stop looking up for the answers. Maybe we need to look at one another to see the real problems, and find the real solutions. And it’s going to take much more than pointing fingers to get our heads above water.